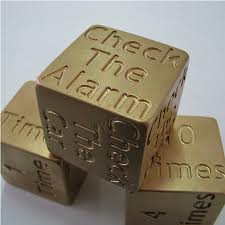

I don't remember if I did that or not...

OCD is a type of anxiety disorder that involves intrusive, uncontrollable thoughts and fears that can eventually take over the person’s life. Although to others the OCD sufferer may seem paranoid or even psychotic, in most cases the person realizes their thoughts and actions are irrational, making them feel even more alienated from those around them. It’s one of the more common mental illnesses, diagnosed nearly as often as asthma and diabetes. It’s important to note that OCD is different from other compulsive behaviors like overeating, gambling or sex addiction, where the person derives at least some short-term pleasure from the behavior. OCD sufferers get no pleasure or satisfaction from their behavior, yet they find it impossible to stop. OCD sufferers may also be diagnosed with conditions like Asperger syndrome, bulimia, social anxiety disorder, Tourette syndrome or major depressive disorder, among others.

It’s believed to have biological roots, and has been associated with abnormalities with the neurotransmitter serotonin, which is thought to have a role in how the brain regulates anxiety. This sort of imbalance of serotonin may be related to abnormal brain development; it’s suspected that children who have had a Group A streptococcal infection may be more prone to OCD later in life.

What Are OCD’s Symptoms?

OCD manifests itself in a set of compulsive behaviors that give the person “relief” from their anxieties. A typical person with OCD might be preoccupied with disease, God, the Devil or germs, all things that can cause tension and give the person the feeling that their life can never proceed as normal. Other obsessions might involve dirt and contamination; the person may be frightened or apprehensive about things like household chemicals, pets, newsprint, radioactivity, and of course their own bodily secretions or excrement.

Others have sexual obsessions that they can never be rid of, or may be extremely averse to sex. An OCD sufferer knows that their thoughts, behaviors and habits are out of step with the rest of the world, which just feeds their anxieties and doubts even more.

Typical obsessive behaviors or rituals might include:

· Skin picking

· Hair plucking

· Counting, which can come into play by counting specific things (such as footsteps or floor tiles) or counting specific ways (odd or even numbers, for instance)

· Hand washing or showering

· Throat clearing or verbal tics

· Behaviors that are preoccupied with order, such as putting items in a straight line, touching objects a set number of times, turning lights on and off, stepping on only a certain color of floor tile, checking that their car is locked several times over before leaving it, or only walking up or down a flight of stairs in a certain fashion (i.e. always starting and ending on the same foot)

How did it come to this?

Hoarding

Hoarding is an offshoot of OCD that has come to the public eye in recent months with hoarding-related TV shows. Hoarders might think that inanimate objects (teddy bears, documents, electronic devices, anything) are sentient beings with thoughts and emotions. In other cases, hoarders might never be able to break associations between those objects and a person or a past phase of their lives, and hang onto them as “mementos” or “keepsakes.” Often this might be linked to the trauma of a death or divorce. Nonetheless, hoarding can be just as destructive and just as crippling as any other form of OCD.

Management And Treatment

The first line of treatment for OCD has always been psychotherapy (and in some cases, dynamic psychotherapy). Newer therapies, though, have involved behavioral modification and medication. Behavioral modification for OCD might involve “exposure and ritual prevention,” where the person gradually is conditioned to let go of the anxiety associated with neglecting to go through their ritual behavior. The person might touch something only mildly “contaminated,” or might check the lock on their house only once when leaving, rather than going back and rechecking it. From there, the person is habituated to tolerate their anxiety in increments (touching something a little more “contaminated,” not checking a lock at all or only washing their hands once instead of repeatedly).

Other behavioral work has concentrated on “associative splitting” to reduce obsessive thoughts. It’s a concept that encourages neutral or positive associations in the network of OCD-related anxieties. For instance, a person who is obsessed with fire meaning “danger” or “destruction” might instead be steered towards thinking of fire as fireworks, fireflies, fireplaces, candlelight dinners, campfires or other pleasant associations.

The brain chemistry involved with OCD suggests using SSRI type drugs (selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors) such as paroxetine, fluoxetine, escitalopram or tricyclic antidepressants such as clomipramine. SSRI’s block excess serotonin from being directed back into the original neuron that released it; instead, they bind serotonin to receptors of nearby neurons, sending chemical signals that can help head off anxiety and obsessive thinking. Some newer-generation antipsychotics have been found useful in treating OCD; paradoxically, some of these drugs have been seen to cause obsessive-compulsive symptoms in patients who didn’t have OCD before.

Some experimental drug treatments have been observed to act on serotonin and neurotransmitters:

· The naturally occurring sugar inositol

· Vitamin and mineral supplements (some believe that nutritional deficiencies contribute to OCD)

· Opioids such as morphine and synthetics such as tramadol. It’s not clear exactly how these work, but they sometimes rapidly alleviate OCD symptoms

· Psychedelics such as LSD and peyote

· Nicotine treatment (again, the jury is still out on this one)

· Anticholinergics, to head off the anti-dopaminergic effects of choline

Will I ever be myself again?

Although there is still a lot of research to be done on OCD, the last several years have seen significant advances. Medical science has gone a long way towards understanding the biological roots of OCD; between treating the root causes and readjusting the behaviors of the OCD sufferer, many with OCD (and many with related anxiety disorders) have been able to go back to leading a fairly normal, routine life again.